The Euro’s Origins and Stablecoin Challenge

Why the euro lags the dollar and how stablecoins could help

The euro stands as one of humanity’s most ambitious monetary experiments, a tangible symbol of a continent’s unwavering commitment to peace and economic integration. Yet, this very genesis, born from a unique historical imperative, now presents a distinct paradox in the burgeoning world of digital finance: why is it so much harder for the euro to foster a robust stablecoin market compared to its dollar counterpart? The answer lies deep within the euro’s DNA, an intricate design prioritizing internal alignment over external domination.

In this edition, we delve into the Euro’s founding principles and structural origins to understand why they create fundamentally different dynamics for Euro stablecoins compared to other currencies.

Post World War II: The Euro’s Origins, American Strategy Meets European Necessity

The euro’s creation story begins not in Brussels or Frankfurt, but in Washington. After two world wars that had devastated Europe and drawn America into costly overseas conflicts, US policymakers recognised that European stability required more than military occupation or Marshall Plan reconstruction. The Cold War’s emergence made this imperative urgent: America needed a unified, economically robust Europe to help contain Soviet expansion without requiring perpetual American intervention.

The US became the chief architect and supporter of European integration from its earliest stages. The European Coal and Steel Community, launched in 1951, bore American fingerprints throughout. American officials understood that binding France and Germany together economically would make future conflicts impossible, sparing the US from having to cross the Atlantic a third time to referee European disputes. This was less altruism than strategic necessity: a fragmented Europe would remain a security liability and economic drain on American resources.

1960-1970s: The Deutsche Mark’s Dominance and French Frustration

European integration progressed through the 1960s and 1970s, but monetary cooperation revealed uncomfortable truths. The Werner Plan in 1970 was the first serious attempt at monetary union, though it failed due to the oil crises and economic instability of the 1970s.

Under the European Monetary System established in 1979, member countries maintained fixed exchange rates within specific bands. In practice, this system gave Germany’s Bundesbank effective control over European monetary policy. Other countries, particularly France, found themselves constantly adjusting fiscal and monetary policies not to serve their domestic needs, but to maintain their currency’s parity with the deutsche mark.

This arrangement proved politically toxic in France. French taxpayers grew weary of fiscal restraint imposed not by their elected government’s economic judgement, but by the need to keep the franc aligned with German monetary policy. The system created what economists would recognise as an unsustainable hierarchy: Germany could set policy based on its domestic priorities while other countries bore the adjustment costs.

1989: Mitterrand’s Bargain, German Reunification for European Integration

The Berlin Wall’s fall in 1989 created an unexpected opportunity to resolve this tension. German reunification required consent from the three Western occupying powers: the US, Britain, and France. President François Mitterrand of France saw his chance to extract a historic concession.

Mitterrand’s offer, based on the Delors Report (1989), was straightforward: France would support German reunification, but only if Germany committed irrevocably to deeper European integration. This meant a new treaty transforming the European Community into the European Union, and most crucially, abandoning the deutsche mark for a common European currency. Chancellor Helmut Kohl, understanding that reunification was Germany’s paramount national interest, agreed.

1992: The Maastricht Struggle: Democracy Meets Geopolitical Necessity

The Maastricht Treaty of 1992 outlined the path to monetary union through specific convergence criteria, including limits on inflation, government deficit, government debt, exchange rate stability, and long-term interest rates.

Treaty negotiations began in 1992 and proved tortuous. The United Kingdom signed the treaty but secured an opt-out from the common currency. Denmark initially rejected the entire treaty in a referendum, forcing renegotiation of special provisions before a second, successful vote. Most dramatically, France’s referendum passed by merely 1.05 percentage points—a result saved only by Mitterrand’s commanding television performance in the campaign’s final days.

Its process unfolded in three stages: Stage 1 (1990-1994) focused on free movement of capital, Stage 2 (1994-1999) established the European Monetary Institute and convergence programs, and Stage 3 (1999) saw the launch of the Euro for electronic transactions and the establishment of the European Central Bank.

Economic Warnings Ignored

Along the way, leading economists raised fundamental objections to the euro project. Robert Mundell’s optimal currency area theory suggested that monetary union without labour mobility, fiscal integration, or similar economic structures would create persistent imbalances. Critics argued that countries with different productivity growth rates, business cycles, and economic structures couldn’t share a currency without causing chronic problems.

These warnings were dismissed by political leaders who assumed the euro would accelerate economic and political convergence. The theory was that monetary integration would force structural reforms and drive productivity gains in lagging regions, creating the optimal currency area conditions post hoc rather than requiring them as preconditions.

January 1st, 2002: Finally, the launch

The Euro was introduced for electronic transactions on 1 January 1999, with eleven founding members: Germany, France, Italy, Spain, Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, Austria, Portugal, Finland, and Ireland. Greece joined in 2001. Physical Euro banknotes and coins were introduced on 1 January 2002.

As a side note, which gives views on the approach, while the banknotes feature a common design across all Eurozone countries, the coins have a common “European” side and a national side. This national side allows each country to stamp its own currency with its own images, often depicting symbols of national pride, historical figures, or significant landmarks.

The project represented one of the most ambitious monetary experiments in modern history, creating a single currency for countries with different languages, cultures, fiscal policies, and economic structures - something unprecedented in peacetime.

2002-Today: The Convergence That Never Came

The expected convergence of economic and political agendas largely failed to materialise. Instead, the euro created two distinct problems that persist today.

First, the 2011 sovereign debt crisis demonstrated how monetary union without fiscal union creates systemic vulnerabilities. Countries like Greece, Portugal, and Spain couldn’t devalue their currencies to restore competitiveness. Instead, they faced deflationary internal adjustment—cutting wages, pensions, and public spending—to regain competitiveness within the eurozone. This process proved economically devastating and politically explosive.

Second, the euro created persistent trade imbalances that benefit some members at others’ expense. Germany’s industrial sector enjoys what economists call a “beggar-thy-neighbour” advantage: it exports manufactured goods priced in euros weakened by southern European economic struggles. Meanwhile, southern European countries find their exports priced in euros strengthened by German industrial prowess, making their goods less competitive globally.

A Unique Institutional Framework: The Eurosystem and the Missing Treasury

The Eurozone also has a unique institutional design. The monetary authority for the euro is the Eurosystem, which functions as a federal-style network. At its heart is the European Central Bank (ECB), headquartered in Frankfurt, Germany. The ECB is the strategic brain, responsible for setting the single monetary policy—such as key interest rates—for the entire Eurozone with the primary objective of maintaining price stability.

Unlike the Federal Reserve or People’s Bank of China, the ECB operates in a complex multi-layered system, it does not operate alone. It works hand-in-glove with the National Central Banks (NCBs) of each member country, such as Germany’s Bundesbank, Banque de France or the Bank of Italy. The ECB sets monetary policy for the entire eurozone, but implementation occurs through national central banks that retain some operational independence. This creates potential coordination challenges that don’t exist with truly unified central banks. The NCBs act as the operational arms of the Eurosystem. They implement the ECB’s policies on the ground, conducting open market operations, holding foreign reserves, and interacting directly with the commercial banks within their national borders. This structure was a brilliant political compromise, allowing member states to retain their prestigious national banks while ceding monetary sovereignty to a central authority.

There is also a critical missing piece to this puzzle: there is no single European Treasury. Unlike the US, which has a federal Treasury Department that issues debt for the entire country or People’s Bank of China which operates as a traditional national central bank under direct government control, with clear political oversight and coordination with fiscal policy, the ECB cannot directly finance governments (unlike many national central banks during crises), and cannot act as lender of last resort to individual countries, and must balance the interests of 20 different economies with varying needs. Fiscal policy—the power to tax and spend—remains firmly in the hands of individual national governments. Each of the 20 Eurozone countries has its own ministry of finance and its own treasury that issues its own national debt. This institutional setup is the direct cause of the fragmented sovereign bond market and the absence of a unified “Eurobond,” which is the core challenge for creating deep, liquid euro stablecoin reserves.

Why the Eurozone Underperforms

These structural flaws explain why eurozone aggregate performance has remained below potential since 2008. The absence of automatic fiscal transfers means that economic shocks hit different regions asymmetrically without compensating mechanisms. Germany cannot expand fiscal policy to boost demand for southern European exports because it has no fiscal authority over those countries. Meanwhile, southern European countries cannot restore competitiveness through currency devaluation.

The result is a monetary union caught between two stools: too integrated to allow individual countries to pursue optimal national policies, but not integrated enough to pursue optimal union-wide policies. This creates persistent unemployment in some regions, persistent trade surpluses in others, and suboptimal growth for the eurozone as a whole.

Can Stablecoins Correct These Imbalances?

The structural challenges facing euro stablecoins—particularly the absence of a unified safe asset—mirror the eurozone’s broader institutional gaps. If you back your EUR stablecoin with bonds, which country would you pick?

Stablecoins might offer unexpected solutions to some of these problems.

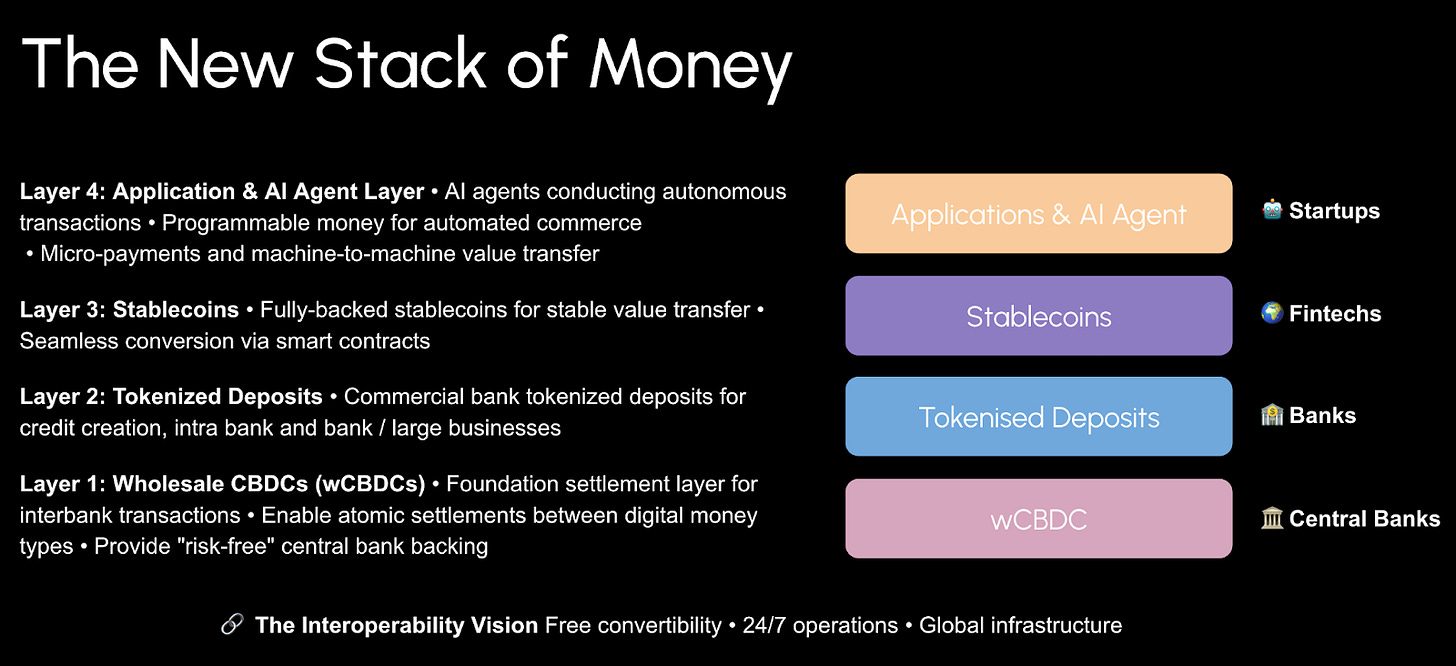

First, wholesale central bank digital currencies (wCBDCs) backing euro stablecoins could create the unified safe asset that the eurozone has always lacked. Rather than managing portfolios of fragmented national bonds, tokenised deposits and stablecoin issuers could hold digital euros directly from the ECB, creating true monetary union in the digital sphere.

Second, programmable stablecoins could enable automatic fiscal transfers that the current system lacks. Smart contracts could direct transaction fees or yields towards regions experiencing economic stress, creating the stabilising mechanisms that optimal currency areas require.

Third, the global nature of stablecoin markets might force the eurozone towards greater integration. As dollar stablecoins dominate digital finance due to their superior backing assets and unified regulatory framework, competitive pressure might finally drive the political compromises necessary for deeper fiscal union.

We envision a new monetary stack encompassing wholesale CBDCs, Tokenised deposits, stablecoins and application layers - this stack could prove to be in particular the perfect system for Europe.

Conclusion: The Euro, A Monument to Peace, A Bridge to Digital Unity

The euro’s greatest achievement isn’t measured in GDP growth—it’s measured in the wars that never happened. For over two decades, this currency has fulfilled its most essential promise: making conflict between eurozone members literally unthinkable. No generation in European history has enjoyed such sustained continental peace.

The euro was designed as an instrument of peace, not economic optimization. Its architects prioritized political binding over financial efficiency—conscious choices that created today’s structural complexities. The euro will never be the dollar, and that’s precisely its strength. Where the dollar dominates through economic might, the euro endures through democratic legitimacy and shared sovereignty.

This unique genesis means European digital finance cannot simply copy American models. The fragmented bond markets that challenge euro stablecoin design represent something profound: twenty democracies that chose to limit monetary sovereignty for continental peace. The absence of a European Treasury preserves national democratic control while enabling monetary cooperation.

The digital euro stack we envision—wholesale CBDCs, tokenised deposits, and programmable stablecoins—offers an unprecedented opportunity: completing the euro’s integration mission through technology rather than political revolution. Smart contracts could deliver the automatic stabilisers that politics has prevented. Digital infrastructure could create the unified safe assets that constitutional constraints have precluded.

Most importantly, this evolution preserves what makes the euro unique: democratic legitimacy, federal structure, and commitment to shared rather than hegemonic sovereignty. The euro was born from a revolutionary idea—that former enemies could share money and make future conflicts impossible. Digital technology now offers the chance to perfect that revolution.

The euro stands as humanity’s greatest monetary peace project. Its digital evolution promises to be its greatest technological one.

Subscribe to Euro Stable Watch if you don’t want to miss the next issues 💶

Recommended in the euro stablecoin space:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Euro Stable Watch to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.